Two recent Salt Lake City performances once again highlight the creative entrepreneurial impact of the Utah Enlightenment.

Two recent Salt Lake City performances once again highlight the creative entrepreneurial impact of the Utah Enlightenment.

Talkbacks after a performance or a screening of a new film can be risky, frustrating and deflating. There are plenty of justifications why many creative professionals hesitate to moderate discussions after the presentation, especially if superficial, irrelevant questions and sentiments dominate the exchange. This especially can be a risk if the theme of a piece touches on subjects that easily can confound an individual’s capabilities to respond sensitively and without awkwardness.

It was an audacious move for choreographer Dan Higgins to proceed with a talkback following the performance of In. Memory. Of., An Evening of Storytelling and Dance, an acute, personal representation of the internal and external nature of mental illness and trauma. As audience members waited for the dancers to return to the stage for the panel discussion moderated by Dr. Shannon Simonelli, a local specialist in creative arts therapy, the sensations of the just-concluded piercing, emotional performance still were palpable.

Higgins and his five fellow dancers made an indelible mark among the audience members in the Black Box Theatre of the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. Simonelli did a marvelous job of moderating the discussion. And, the comments evidenced that Higgins’ work had achieved the impact any creative artist strives for in connecting to an audience. The work struck lucid, relevant, memorable, robust and impassioned tones in every way possible.

When Higgins presented the premiere rendition of the work last summer at the Great Salt Lake Fringe Festival, there already were the essential elements of clarity in capturing the pendulum swings of depression and trauma through dance movement, accompanied by instances of spoken text and music. But, in the intervening six months leading up to the performances that were part of Repertory Dance Theatre’s Link Series, he expanded In. Memory. Of. with a duet (performed by Natalie Border and Higgins) along with many fine brush strokes that raised the bar of the piece’s artistic impact by significant degrees of magnitude.

There were other changes. Among them were two new dancers (Betheny Shae Claunch and Lyndi Coles) who joined Higgins and three dancers from the 2017 premiere (Border, Micah Burkhardt and Jalen Williams). After observing three open rehearsals, there were no questions about how intrinsically attuned the ensemble had become. Higgins had learned from the experience prior to the Great Salt Fringe Festival performance last summer. At that time, the creative process had been accelerated to produce a 55-minute work in just a few weeks. And, there was a personnel change just two weeks before the premiere. The performance and the work certainly drew the proper attention but Higgins also appropriated wisely the lessons as an effective choreographer.

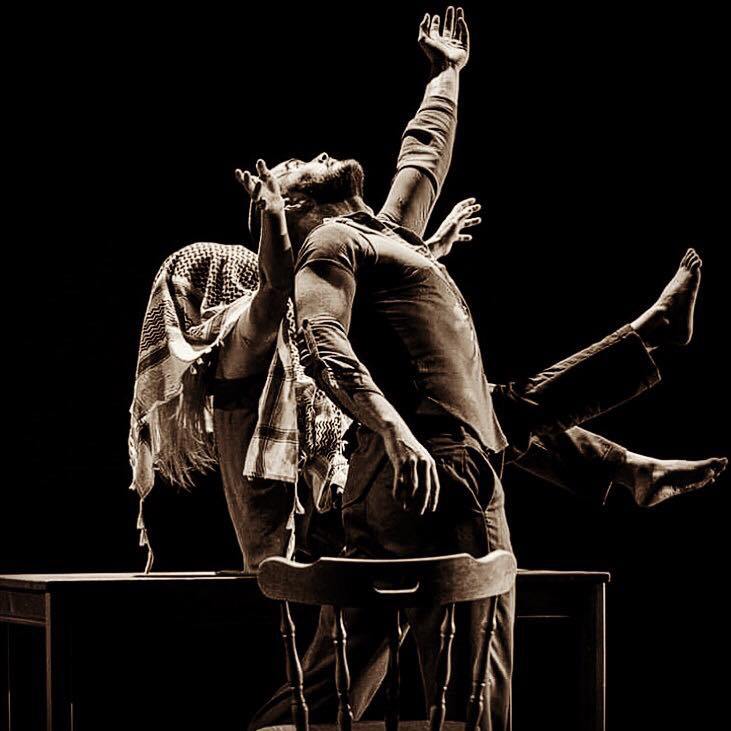

The evidence of their preparation defines this latest performance, a fine 70-minute example of how the dancers imbued the entrainment phenomenon so prominent in ensemble performances that click into an electrifying vibe that fills the theater. The dancers synchronized their own distinct external rhythmic senses as well as their own inner pulses and nonverbal communication, most prominently in the eye contact the performers consistently made with each other. The dancers were invested emotionally and socially in each other, as colleagues and as performers. But, even more remarkable is that there were many moments in the work, which demanded the dancers to be vulnerable — even impotent and confrontational — toward each other. Off the stage they would never contemplate doing so as artists who respect each other deeply. But it was a critical dynamic that Higgins pushed for in rehearsals and the results proved it.

Thus, it was a mutual artistic pact for the ensemble, which brought credibility and authenticity to its performance and the audience knew it. When the dancers joined the talkback on stage after the performance, one could see how they had carried juxtaposed feelings of exhilaration, exhaustion and ardor for their work.

And, only later did audience members realize that the performance actually began before its scheduled start. As they took their seats, Higgins sat silently at a desk, his back facing the audience, and a scarf spread out on the table. It’s a shrewd creative choice. As he explained later, the setting primed the start of the emotional journey for him, as he could hear the small chatter among audience members as they settled in for the show. Higgins channeled all of this for the performance, as he connected the audience emotionally to one of the most important metaphors of the work – the wolves, always keenly observant and omnipresent, even when they are not immediately visible.

The company of dancers communicated the metaphors with consistent clarity, especially in the sections of the work when there is no music. Indeed, the soundscape at some points is barely more than the loud breathing that goes with the physical exertion, as dancers push their limits throughout the piece. There are moments of frenetic movement and paranoia, as Higgins appears to check windows or as dancers fear a predator might be near. There are moments when the movements deliberately convey a tenuous sense of control which could be lost at any moment.

The scarf is an integral prop in virtually every moment of the work and its paradoxical meanings shifting continuously. It represents memories – some soothing and others traumatic. It’s a blanket of security or one of trauma. It’s an accessory to cover up vulnerability, shame or weakness and then it’s an instrument of struggles in emotions. The soundscape collage is just as complex despite its stark simplicity. There are musicsl moments of lyrical ambience and then steel iciness, interspersed with pings, percussive roars, and one cacophonous excerpt so brutal that it jars the listener into the proper reaction.

The duets, which become proxies for the inner confrontations for one’s mental well-being, inspire equally the tenderest emotions and the most vulnerable and uncompromising sensations. Higgins achieves many effortless transitions throughout the piece. One extraordinary example occurs late in the work with Higgins on the ground and letting out an anguished scream, which immediately segues into the next section of dance movements. Likewise, in the text (written by Cooper Smith and Marty Higgins), Higgins occasionally mumbles in a barely audible voice, as instructed, but then his voice rises to a near-piercing level that it rightly startles the audience.

The work’s cathartic elements affect dancers and audience members similarly. Higgins created the work from his own experience, as the aspects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) have affected his family. Higgins’ late father served in Vietnam with the U.S. Special Forces as a Green Beret and the young artist only learned the whole story of the struggles his father experienced after he died. As noted in a previous article at The Utah Review, Higgins said his father always hid his struggles, convinced that being seen as vulnerable is a sign of human weakness that can never be overcome.

Simonelli, who was joined by Dr. James Asbrand, a Salt Lake City psychotherapist who works with many veterans, noted how such artistic experiences can begin to help individuals and family members understand and cope with the pain on the path toward healing and breaking away from the illusions of our habitual thinking about mental illness.

Higgins, an RDT dancer, is among a new generation of creative entrepreneurs in the Utah Enlightenment. To realize this work, he conducted a crowdfunding campaign and secured the support not only of RDT but also of local organizations including the Volunteers of America, The Road Home, The Rescue Mission of Salt Lake City, National Alliance on Mental Health, The University of Utah’s department of neuropsychiatry and the Utah Department of Veterans and Military Affairs. Pilar Davis handled lighting and stage manager duties for the performances. For his efforts along with those of the other dancers who fully invested themselves as professionals, In. Memory. Of. takes its merited place in the canon of definitive works of dance movement theater.

The emphasis in NOVA Chamber Music Series’ Micro-Concerto program was not on pretty sounds but on commanding performances featuring a lot of technical bravura and musical ideas based heavily on muscled strength rather than on gentle lyricism.

The Ulysses String Quartet quickly established the musical rule of the day with its performance of Beethoven’s String Quartet in F minor, Opus 95, also known as Serioso, which the composer completed in 1810. It is one of Beethoven’s most compact pieces for string quartet that dispatches musical ideas and themes quickly with a good bit of tension. And, the musicians (Christina Bouey and Rhiannon Banerdt, violins; Colin Brookes, viola, and Grace Ho, cello) put the appropriately impassioned fury on the work, starting with the tempestuous opening of the first movement. Their body movements and gestures emphasized the disciplined attaca feel to the work, especially in rhythm, while preserving the piece’s emotional restlessness.

That disturbed sensation carried over into the second movement, as Ho opened with a solo descending motif on cello. Every attack is crisp, even in the Allegretto, the difficult movement that follows. Finally, the quartet certainly kicks it up a notch in the dazzling passages of the closing bars, which Beethoven set in F major.

Dazzling also is the proper descriptor for the performance of Steve Mackey’s Micro-Concerto for Percussion and Mixed Quintet, a 1999 work that really switches up the roles of solo and accompanist. Keith Carrick, Utah Symphony’s principal percussionist for the last six years, stole the performance with effortless virtuosity. Indeed, the percussion set-up for the work overwhelms the space, which includes vibraphone, marimba, bongos, metal percussion and sundry items including utensils and toy whistles. Bouey and Ho from The Ulysses Quartet joined Jason Hardink, pianist, and the two wind players: Mercedes Smith on flute, piccolo and alto flute, and Katie Porter, clarinet and bass clarinet.

It was a superb performance for the work which Mackey completed in 1999. The work’s five movements pick and drop musical ideas quickly, many of which have distinct rock and jazz inflections. The opening comprises small strokes and dots of musical colors and textures from the players which might remind which might remind listeners that Mackey in this work represents the musical parallel of French painter Georges Seurat. Carrick and the ensemble evince a extensive spectrum of musical textures and timbres that alternate between pleasing and invigorating. The vibraphone solo glistened and the marimba and cello interlude of the fourth movement provided some of the most expressive moments of the concert.

That pointillist aesthetic is explored even further in Morris Rosenzweig’s …snip, snip …, which was given its premiere as a NOVA commissioned piece for its 40th anniversary. Rosenzweig, distinguished professor of music at The University of Utah, was tapped to write the work, which was made possible by the Chamber Music America classical commissioning program.

Listening to the work, conceived in six short movements that are completed within a 15-minute span, underscores the composer’s own description – in which musical ideas are laid out, sorted into patterns and then sewn (synthesized) by a skilled tailor. Rosenzweig, a New Orleans native whose family lineage includes many skilled tailors, offers up a wonderful example of letting the listener’s ears and mind absorb and blend the ranges of musical colors, tones and textures, as he or she might see fit.

The work was conducted by Devin Maxwell and performed by The Ulysses Quartet who were joined by Katie Porter on clarinet, Stephen Proser on horn and Jason Hardink, who switched frequently between piano and prepared piano. The ensemble makeup in the score is a refreshing deviation from the typical ‘unusual’ instrumental combinations that have been found especially in many of the most famous chamber ensemble works of the previous century. And, with the specified instrumental forces, Rosenzweig’s soundscape emerges in bracing form with an optimal mix of all sorts of musical snippets.

The closing work brought the program’s theme full circle with the Septet for Horns and String Quartet, Opus 81b, which Beethoven completed in 1795 at the age of 25. The Ulysses Quartet returned to the stage along with soloists Edmund Rollet, Utah Symphony’s acting principal horn player, and Stephen Proser, who has been with the Utah Symphony for more than 25 years.

But, it was the presence of Corbin Johnston, contrabass who has been associate bass principal with the Utah Symphony since 1999, which fortified the work’s commanding and authentic performance. Clearly, the young Beethoven composed a chamber piece that was more in line with the style of Mozart or Haydn than with his later works, which broke completely from older classical traditions. Thus, it was common practice to score parts for cello and contrabass in such chamber works, which is what Beethoven did originally. Only later did publishers issue editions that omitted the contrabass part. The original version was restored only within the last decade, thanks to the efforts of Egon Voss, a German musicologist.

Kudos are deserved for returning to the original scoring because the balance between the strings and the pair of horns, whose virtuosic passage work produces a great deal of sound, was perfect.